Introduction

The most common fire protection systems, other than fire sprinkler systems, are fire alarm systems. Unfortunately, there is probably the most confusion surrounding fire alarm systems than any other fire protection system. This is because the systems themselves can range from relatively simple, to extremely complex electronic systems that interface and control many other building systems.

Smoke Detectors vs Smoke Alarms

Most people are familiar with the smoke detectors that are installed inside their homes. If the home is relatively new, these smoke detectors are hardwired on a common branch circuit. Because they are all hard wired together on the same branch circuit, when one detector activates, all of the smoke detectors in the house alarm simultaneously. So, to clear things up, a device that detects smoke and alarms at its own sounder base, and is not connected to a fire alarm control panel, is called a smoke alarm. Within homes, smoke alarms are installed in houses within bedrooms, outside of each bedroom area, and on each story, except for attics. Smoke alarms are also required in commercial residential buildings, such as hotels, motels, apartments, boarding houses, and essentially every residential type of building.

Definition of a Fire Alarm System

On the other hand, a building fire alarm system is a network of control equipment, initiating devices, control interfaces, monitoring interfaces, notification appliances within the building, and signaling equipment that transmits fire alarm data to an off-site location. The initiating devices are alarm triggering devices such as manual pull stations (these are common in schools), smoke detectors (not smoke alarms), heat detectors, fire detectors, valve tamper switches, and waterflow switches for sprinkler systems. These initiating devices send an alarm signal to the fire alarm control panel (FACP), and the FACP decides what to do with the alarm signal, which is based on its programming. For example, the FACP may cause all of the audible and visual alarms throughout the building to activate, may send a signal that eventually routes the local fire department to the building, or send a supervisory signal for a technician to check a valve that might have been accidentally closed. The fire alarm system can also do many other complex tasks, such as:

- Shut down heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) equipment

- Initiate a specialty system such as a smoke control system

- Actuate fire/smoke dampers automatically or manually

- Close special fire rated doors to close openings

- Trigger a releasing panel that activates many sprinklers simultaneously (i.e., a deluge type sprinkler systems)

- Control the operation of elevators

- Shut down elevators

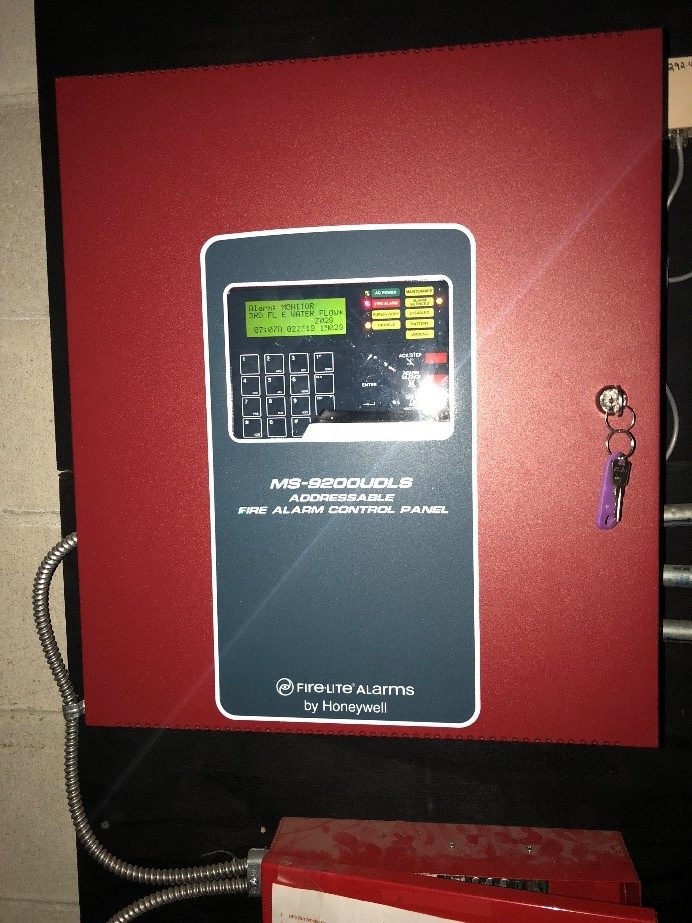

Figure 1 shows a picture of a typical fire alarm control panel that is installed in a medium sized building. The array of FACPs available on the market is daunting, and the people most familiar with such equipment are the sales representatives who sell such equipment, or the technicians deployed to program or install the panels. The modern FACP is much like a computer. Older FACP were electric devices that relied on relays and more primitive electric technology, and could not perform the tasks that modern FACPs perform.

Figure 1: Typical Fire Alarm Control Panel

When is a Fire Alarm System Required in New Buildings

Since a basic idea of what a fire alarm system has been given, the next question is “When are fire alarm systems required to be installed in buildings?” The answer to this question rests within Section 907.2 of the International Building Code, or its locally mandated equivalent. This section is only for new buildings. Retroactive requirements and when and where fire alarm systems are required in renovation projects is a little more complicated, and will be discussed in later articles. Whether or not a fire alarm system is required is based on three things: occupancy and use group, occupant load, and the details of the level of exit discharge. For example, in the 2015 IBC, in a Group F (e.g., a factory that manufactures things) occupancy, a fire alarm system is required if it is more than two stories or if it has a combined occupant load above or below the level of exit discharge. Another example, is that a store with a combined occupant load on all floors is greater than 500 requires a fire alarm system. The reader is encouraged to read Section 907.2 in its entirety for all cases where a new building would require a fire alarm system.

Sometimes, a fire alarm control unit is required for specialty functions that do not require the entire building to have a complete fire alarm system. A complete fire alarm system is one that has not only the initiating devices, but also the entire building has notification devices (speakers and strobes) installed throughout the building. In two common cases, a fire alarm control unit is required to relay signals off site or to a constantly attended location within the building. The two cases are to monitor an automatic sprinkler system, and to control elevator functions. These units are localized to these functions only, and do not require a fire alarm system throughout the building, unless one of the Section 907.2 requirements apply.

Figure 2: Atrium Smoke Detector and Sprinkler Heads

Sprinkler systems are actually part of the fire alarm system. When any single sprinkler head within a sprinkler system activates, its system waterflow triggers a detector that sends an alarm signal to the FACP. The FACP then sends an evacuation alarm throughout the building, and a remote signal that eventually dispatches the fire department to the building. Figure 2 shows an atrium with sprinkler heads and smoke detectors installed. In this building, both the sprinkler heads and the smoke detector trigger an evacuation alarm, and also activate the atrium smoke control system.

How Fire Alarm Systems Are Designed

Once it is determined that a fire alarm system is required, there are standards that dictate how a fire alarm system has to be designed, installed, inspected, tested, and maintained. The main standard on how to do this is NFPA 72, National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code. The latest edition of NFPA 72 clocks in at 411 pages, and is very technical in nature.

The other standard that is required to design fire alarm systems is the National Electrical Code, or NFPA 70. NFPA 70 specifies the finer details of the basic electrical/electronic elements in fire alarm systems: cabling, wiring, wiring methods, branch circuit control and over current protection devices, junction boxes, conduit, etc.

Fire alarm systems are designed by either technicians with specialized training and certification in fire alarm systems design or by professional engineers with expertise in fire protection and electrical engineering. The most widely used technician certification system is the one used by the National Institute for Certification in Engineering Technologies (NICET). NICET has a tiered system for certification in fire alarm systems certification. A NICET Level III Technician is the minimum required credential for generating approved fire alarm system plans. However, some jurisdictions may require a NICET Level IV technician or a Professional Engineer to prepare and approve fire alarm plans. For example, New Jersey requires that fire alarm drawings be prepared by a Professional Engineer. A NICET III Technician would typically sign their name as John Doe, CET. A NICET IV would sign their name as Jane Doe, SET, where SET stands for Senior Engineering Technician. A Professional Engineer writes their name as John Stoppi, PE.

How Fire Alarm Systems are Installed

The supply circuits, conduit, junction boxes, and branch circuit overcurrent protection devices for fire alarm systems are often installed by the project’s master electrician. This is not always the case, as the fire alarm contractor may install every portion of their system. The fire alarm contractor is normally subject to licensing requirements by the local jurisdiction that are fire alarm specific or just general electric in nature.

What is Allowed to be Installed in a Fire Alarm System

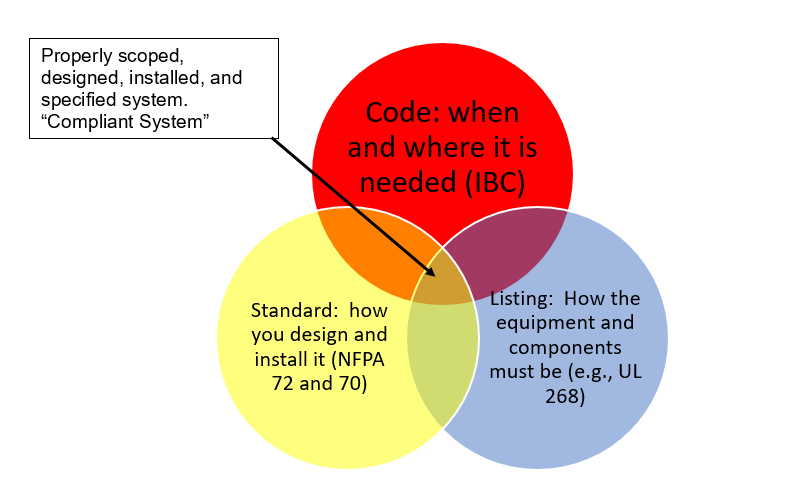

The IBC, NFPA 72, and the NEC dictate specific listings or standards that individual components have to adhere to. For example, a manufacturer cannot just design their own smoke detector and start selling it for legal use in these fire alarm systems. The smoke detectors would have to meet Underwriter’s Laboratory Standard 268. A FACP must meet UL 864. These UL standards are component/appliance specific requirements, testing criteria, and monitoring criteria that devices must adhere to in order to be legal. This system exists for basically all consumer appliances—pull out your toaster or oscillating fan and you will be sure to find a UL certification mark (or equivalent company). Basically, every component in a fire alarm system has to subscribe to a certain standard. The standards are updated from time to time, so manufacturer’s have to update their equipment to stay compliant (and legal).

Figure 3: Venn Diagram of Code, Standards, and Listings

How are Fire Alarm Systems Reviewed and Inspected

In order to permit installation, a fire alarm project needs to be issued a building or fire permit. This happens when engineering documents, shop drawings, or both are submitted to the local Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ). The drawings are reviewed for compliance to the IBC, NFPA 72, NFPA 70, and equipment submittal sheets are reviewed to ensure the equipment is listed, approved, and appropriate.

After a permit has been issued, the fire alarm system is subject to a series of inspections. Typically, there is a rough inspection when wiring and conduit is inspected. Then, there is a final inspection when all devices and equipment are verified, and acceptance testing is performed. The inspector may witness all acceptance testing, or accept documentation for some or all testing in lieu of testing everything with the contractor.

Fire Alarm System Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance

Chapter 14 of NFPA 72 lists all of the acceptance testing required for fire alarm systems. It also lists the periodic inspection, testing, and maintenance that must be performed for the system. After the system has been installed, it becomes subject to the International Fire Code, or its local equivalent. That is, fire inspector’s supervise the inspection, testing, and maintenance program of the fire alarm systems. They witness some testing, or may witness all testing. If there is a particular system that has a history of nuisance alarms, the local fire inspector would be likely to perform a full inspection and develop an inspection, testing, and maintenance punch list. Lastly, insurance companies are interested in these programs, and may offer premium reductions for contracting these duties out to third party companies, which is typically the installing contractor.

Conclusion

Fire alarm systems are a necessary part of many buildings’ fire safety approach. These are complicated systems that are designed, installed, maintained, and inspected by technical experts in these fields. It is uncommon for a single professional to be well-versed in every detail of fire alarm systems. This article was intended to give the layman and others familiar with such systems a holistic understanding of fire alarm systems. The best way to understand more about fire alarm systems is to ask one of the technical experts about their knowledge of the field if you’re lucky enough that they have the time to discuss it with you.

John P. Stoppi Jr., FPE, CEI, CFI is a registered fire protection engineer, a certified commercial electrical inspector, and a certified fire inspector.